Magnificently Brutal

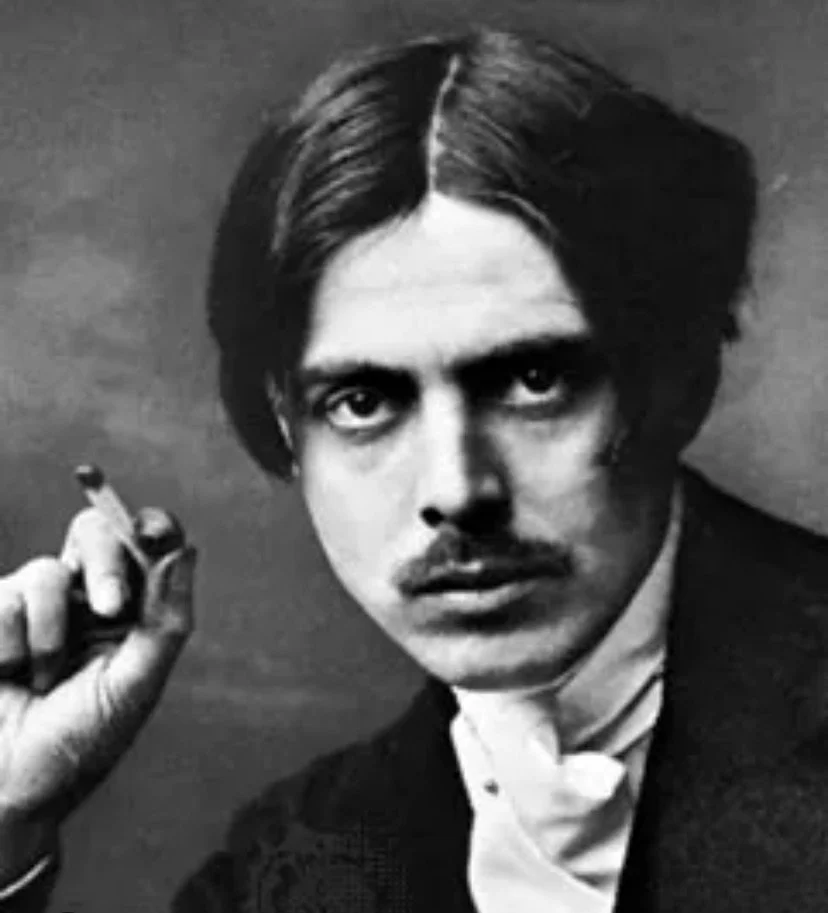

The love life of Wyndham Lewis

‘Magnificently brutal’ was Nancy Cunard’s assessment of Lewis as a lover. Wyndham Lewis was a British painter, modernist writer, critic and the founder of the Vorticist movement. Lewis was a complex character; he was attractive to women but struggled to form lasting emotional relationships. The most important woman in Lewis’s life was his mother. After his father abandoned the family when he was ten, mother and son formed an intense relationship. In his correspondence to her he addressed her as a contemporary and a friend; he bragged of his sexual conquests and expected her to be proud of him. He also reassured her that his girlfriends were no serious threat to their own relationship.

Lewis had unusual views on marriage and family life. During his time in Paris in the early 1900s, Lewis was a friend and disciple of Augustus John. Lewis emulated John in his dress, his black cape and hat. Lewis was known as the ‘poet’ to John and felt insecure as a painter. Lewis was very critical of John’s domestic arrangements which involved a wife, Ida and a mistress Dorelia and several children. He wrote ‘Mrs John is no longer pretty, and I no longer have any pity for her:- I don’t see how John could do otherwise than perquisition another woman:- but she seems changed…I don’t like her a bit.’ After Ida’s death in 1907 following childbirth, Lewis took a dislike to Dorelia. He wrote of her ‘as the sickening bitch he (John) has attached himself to’ and ‘who is muzzling his genius.’

Lewis formed several important relationships with older male artists and writers, possibly in the role of surrogate father; Augustus John was an important role model as was the poet Thomas Sturge Moore. Another young artist vied with Lewis to be John’s protégé. This was Henry Lamb, who had abandoned his medical studies to pursue life as an artist. John thought him a fine draughtsman. He invited Lamb and his young wife Euphemia to come and work with him in Paris. Lewis’s nose was put out of joint, he complained,

‘John has a very disagreeable set of people around him just now, and the average morality, taste, sensibility, or whatever one calls it of the average medical student who has read Nietzsche prevails among these persons.’

Shortly after Ida’s death, John’s mistress Dorelia eloped with Henry Lamb. Lewis’s response to this is recorded in a letter from WB Yeats to Sturge Moore,

‘I met a young poet called Lewis who is an admirer of Augustus John…He says that John’s mistress (Dorelia) has taken another admirer, a very clever young painter (Lamb) who does not admire John’s work, and this influences her, and so she does not give John the old ‘submissive admiration’, and this is bad for John, and she has done it all for vengeance because John will not marry her. Lewis is very angry and thinks John should leave her. What does he owe her or the children?’

Did Lewis’ view of a relationship require his lover to ‘submissively admire’ him? Could any of his lovers compete with the total admiration his mother gave him. His mother worshipped him and believed in his genius and dedicated her life to him. During his period in Paris, Lewis was in a relationship with a German woman named Ida Vendel, but he kept her existence hidden. Ida complained to him ‘you always try to hide me in front of your friends, why, are you ashamed of me?’ This closeting of his sexual partners was a feature of most of his relationships. His relationship with Ida was serious enough for him to consider marriage, yet most of his friends were unaware of and never met her. After discovering she was pregnant, Lewis wrote to his mother,

‘About Ida, I am in an impasse – a moral cul de sac. God knows what to do. I don’t however look towards marriage as a solution, and suppose that with infinite pain I shall drift away, and other interests eventually help me to forget the strongest and most unfortunate attachment I’m ever likely to have.’[1]

Lewis used to visit Sturge Moore at his house in Hampstead for poetry readings. Sturge Moore had warned Lewis not to let women use the ‘slop of sex’ to trap him. His advice was that if ‘a man puts his genius between her legs she will cover it with her petticoat and no one will see it again.’ This idea that women would smother a man’s genius was touted by the Austrian philosopher Otto Weininger in his book Sex and Character: An Investigation of Fundamental Principles (1903). He argued that it is the duty of the male, or the masculine aspect of the personality to strive to become a genius and to forgo sexuality; whereas in his opinion the female life is consumed with the sexual function. Weininger argued that human nature could be charted on a sliding scale from ‘total male’ to ‘total female’. Weininger’s system was misogynistic – only those with the greatest concentration of male traits could approach ‘genius’. Lewis and his friends devoured the book and were influenced by its concept of achieving genius.

In 1910 Lewis became involved with Olive Johnson. Olive was an acquaintance of Sickert and John. The relationship produced two children, Raoul born in 1911 and Betty born in 1913. The children were raised by Lewis’ mother, her companion and a nurse. The relationship with Olive lasted until 1918. He was also having an affair with Kate Lechmere during this period. Kate met Lewis in 1912 at a Camden Town Group tea party,

‘I was at once impressed by this striking looking artist, looking much like Augustus John’s early portrait of him. A few days later Lewis invited me to dinner and much to my embarrassment not a word was spoken through the meal, but afterwards on our arrival at the Café Royal (he spoke about Dostoevsky and about himself), I felt instinctively that here was a man of genius, a powerful but complex character.’

Lewis was smitten, he wrote to her ‘I have as many kisses as the envelope will hold. The rest I keep in my mouth for you.’

They set up the Rebel Arts Centre together and it was an important creative collaboration (leading to the production of BLAST and the Vorticist movement) but romantically it was ill fated. Lechmere fell for Lewis’ friend, the critic and philosopher TE Hulme and the pair became engaged. Lewis was jealous and paranoid that Lechmere’s attachment to Hulme would unseat his position at the Rebel Arts Centre.

‘Poor dear Lewis quite lost his head and when he accused me of this Hulme attachment I said that he had shown little attention to me of late and his remark was that it was not too good for a woman to have too much notice taken of her.

During my friendship with Hulme Lewis made himself most unpleasant. Some mornings he would arrive in a very excitable state and rapidly pace up and down the studio calling me a ‘bloody bitch’.’[2]

This contretemps resulted in a famous incident where Lewis threatened to kill Hulme and tracked him down to a house in Frith Street to confront him. However the stronger Hulme dragged Lewis into Soho Square and hung him upside down on the tall iron railings. Lechmere wrote how this incident proved that Lewis was of a suspicious and jealous nature and ‘later he developed a mild persecution mania.’[3]

The overlapping liaisons with Olive and Kate can perhaps be explained by Lewis’ last extraneous paragraph of his novel Tarr. Lewis wrote that his hero had three children with the stout and joyless Rose Fawcett who consoled hm for the lost splendours of his perfect woman, Anastasya. In Tarr which catalogues a version of his love life he introduces us to his new ideal love, Iris Barry.

‘Beyond the dim though solid figure of Rose Fawcett, another arises. This one represents the swing back of the pendulum once more to the swagger side (of sex). The cheerless and stodgy absurdity of Rose Fawcett required as compensation for the painted, fine and enquiring face of prison dishes.’

Lewis’ pattern of having hidden, long-term relationships with some women and more public and exciting affairs with other women suggest that he split his women into domestic and submissive types (who gave birth to his children) like Rose Fawcett and more exciting and dominant women such as Nancy Cunard and Kate Lechmere who corresponded to an idealized Anastasya type of woman. And the sequestration of women such as Olive Johnson and Iris Barry satisfied the demands of his fragile ego.

Iris lived with Lewis from 1918 until 1921. They had two children together (in 1918 and 1920). Lewis kept his liaison with Iris who was thirteen years his junior, a secret. The war had changed Lewis and they were leading an erratic and unsettled life; neither of them wanted to keep the children. During their time together Lewis was pursuing other affairs. When Iris returned from the hospital with their daughter, Lewis was having sex with Nancy Cunard in his studio and Iris had to wait on the steps outside until they had finished. Iris left Lewis and had a successful career as a film critic; in the 1930’s she went to America and set up the Film Library at MOMA in New York.

The Barry/Lewis children ended up in children’s homes and had no contact with their father. Lewis’s biographer Jeffrey Meyers tracked down Robin Lewis Barry (born June 1919), Robin was a tall, thin, handsome, cultured architect who lived in Vincent Square. Born in Birmingham he had been brought up by Iris Barry’s mother until the age of four when he was relinquished to a home for unwanted children. Iris came back into his life in 1950 and gave him drawings and his father’s army identity disc to compensate for her callous treatment of him. He disliked her and never met his father although he had written everything that Lewis wrote. In 1980 he wrote to Meyers thanking him for a copy of his biography and said, ‘Sadly you have not been able to solve the enigma of the man. Maybe this is not possible as he was so much more a poseur than a man that no one will be able to.’[4]

Lewis and Nancy Cunard began their affair in 1920, she wrote,

‘Darling Lewis…I hope you will not forget me in any way either, and I beg you to write to me often…I wish I could see you more often, as in Venice or rather as in the train that day…My real love to you, Lewis.’[5]

Apparently, Lewis disliked Cunard’s preference for anal sex. At the end of her life she wrote that,

‘He was a sort of ‘dominating kind’, and that this kind of ‘persecutedness’ must have been eternal….Perhaps he DID have a more difficult time than many another, I don’t think so. What I will tell you now is this: He was DAMN DIFFERENT to us, the way we feel (I think) towards ‘humanity’. I think on the whole he was half a SHIT. But a great painter, and a splendid letter writer.’[6]

Aldous Huxley penned the characters Myra Viveash and Lypiatt based on Cunard and Lewis in his novel Antic Hay. Lypiatt is a truculent, turbulent, titanic, exultant and extravagantly boastful man but he is also a serious dedicated artist. Sybil Bedford in her biography of Huxley described his relationship with Cunard as failing because,

‘What she wanted were men who were more than a match for her, strong men, brutes’.[7]

There were many affairs. In May 1920, the modernist novelist Mary Butts wrote (in her diary),

‘Wyndham Lewis is the first man I have met whose vitality equals, probably surpasses mine. But he manages it badly – like a great voice badly produced. He is the most male creature I’ve met. I can just keep going with him -or rather have just got going with him. A pleasure to be raped by him – Yes that’s true.’

Mary was to change her opinion on Lewis,

He was crabbed, rude, unkind, ill-bred, unjust. Yet, through it all from The Caliph’s Design and The Childermass, from his drawings and his manifestos, he gives an overwhelming impression of an intelligence at once powerful, searching, original, discontented, wounded, thwarted, maimed, unconquerable.’

There is a theme running through these testimonies of Lewis as a highly sexed and excellent lover but as a difficult and insecure man. His intelligence and vitality seem to have compensated for his shortcomings as a partner. He demanded and received admiration from his lovers, this need may have arisen because of his lack of a father figure to admire him. The emotional damage caused by his father’s departure caused Lewis to be always on the defensive. His persona as an ‘enemy’, his brusque and affronting personality, meant that he often offended a person and turned them against him; in this way Lewis was in control of the rejection. He rejected them before they could reject him.

In the early 1920’s Lewis met Edith Sitwell. Edith got to know Lewis well and observed his mercurial personality,

‘when he grinned, one felt as if one were looking at a lantern slide…a click, a fadeout, and another slide, totally unconnected with it, and equally unreal had taken its place. He was no longer the simple minded artist but a rather sinister, piratic, formidable Dago. For this remarkable man had a habit of appearing in various roles, partly as a disguise and partly to defy his own loneliness.’[8]

One of his favourite roles was the Spanish one in which she said with irony, ‘he would assume a gay, if sinister manner, very masculine and gallant and deeply impressive to a feminine observer.’[9]

It seems that during sitting for his portrait of her, Lewis took liberties with Sitwell, she wrote,

‘He was unfortunately seized with a kind of schwarmerei for me. I did not respond. It did not get very far. So eventually I stopped sitting for him.’

Hence the portrait of Edith has no hands as it was unfinished. The Sitwell’s fell out with Lewis and he mocked them in his book The Apes of God. Edith in later life planned to write an essay about him. In 1931 she penned,

‘One day when he is long dead, I shall write the story of his life. And in it I shall show how every little fault and every little mistake made by this fundamentally gentle and affectionate character is the result of the fear that engrosses him, the fear that he is not loved, the crushing impression that those on whom he has set his affections do not return them.’[10]

Sitwell’s testimony supports the idea that Lewis was emotionally insecure and developed a persona to defend and deflect any slights he received. She uses the word sinister twice to describe him; the apprehension that something bad might happen. I think for Lewis the worst had already happened, the desertion of him and his mother by his father left him with little ability to trust people. He had important mentors like Augustus John and Sturges Moore who he remained faithful to, possibly father figures who he looked up to and was keen to learn from. But the pattern of his relations with women shows him to be a lothario figure, like his father. Whether this was his true nature or an act he conceived (as Sitwell suggests) is difficult to determine.

His thin-skinned temperament and machismo persona are alluded to again by Sitwell,

‘according to himself, (he) is not appreciated, though he even goes so far as to apologize for any little brusqueness that may have been noticed: ‘I’m sorry, if I’ve been too brutal girls’. Now Mr Lewis, not another word. Please, I beg! You know you ought not to spoil them. And besides, the pretty dears like your cave-man stuff. For it is not so often that they meet a real He-man…’[11]

The most important woman in Lewis’s life, his mother, died in 1920. He was still living with Iris Barry, conducting affairs with Nancy Cunard and Mary Butts amongst others. Like his hero Tarr, Lewis was able to see a number of women at the same time and keep them all separate and satisfied. In 1918 at a party given by Gerald Brockhurst, Lewis met Gladys Anne Hoskins, an eighteen-year-old girl from Teddington who was eighteen years his junior. After his separation from Iris, Lewis rented a flat in Paddington and Gladys Anne moved in with him. She had strawberry blonde hair, soft grey blue eyes and ivory skin and became his favourite and loveliest model. He called her Froanna a variation of Frau Anna. She was the ideal wife for Lewis: beautiful and devoted, tolerant of his infidelity and hardship. She was self effacing yet lively; a good housekeeper and superb cook. An inspiring model, efficient secretary, helpful critic and kind nurse.

The timing of his relationship with Froanna is important, they moved in together shortly after the death of Lewis’s mother. There was an emotional vacancy for a woman to dedicate her life to him with the same intensity his mother had done and Froanna accepted the position.

Lewis was a complex man; his childhood experience of his father’s departure from the family and the subsequent enmeshed relationship he developed with his mother created a demanding personality and one who found it difficult to properly connect emotionally with others. His excessive need for admiration charged his love life and his creative endeavours. Lewis’s ideas about genius and the danger of women and sex to genius contributed to his compartmentalizing his life and keeping his relationships hidden. In his neglect of his own children, Lewis was repeating his own experience of an absent father. The women’s testimonies allude to his insecurity, his loneliness and his gentleness. It is only once he is married to Froanna that a more humane Lewis emerges. Froanna wrote,

‘He was a great conversationalist and loved to talk to all kinds of people…He was interested in everything and everybody. Lewis was a very social character who made friends wherever he went.’

The more humane side of Lewis can also be seen in his portraits of the 1930’s which are much softer and sensitive than his portraits of the 1920’s. The portraits of Froanna in particular have an emotional warmth lacking in earlier portraits.

Wyndham Lewis had an interesting and fraught love life; he fathered five children and had little to no contact with them. He both loved and feared women. Only after his mother’s death could he begin to integrate his two ideals of womanhood, the maternal and domestic companion with the more alluring and sexual woman. The three stable pillars in his chaotic life were his mother, his relationship with Froanna and his dedication to art.

[1] WL to Mrs Lewis Feb 1906 in The Letters of Wyndham Lewis (ed Rose) 1963

[2] K Lechmere, Wyndham Lewis From 1912, Journal of Modern Literature, March 1983, p158

[3] Ibid.

[4] J Meyers, The Boigrapher and the Family, The Article, 2020

[5] N Cunard to WL Oct 1922 (Cornell Library)

[6] N Cunard to WK Rose 1963 (Vassar)

[7] From Sybil Bedford’s biography of Aldous Huxley.

[8] E Sitwell Taken Care of: An Autobiography (1965) Hutchinson

[9] Ibid.

[10] E Sitwell diary Cornell University Library

[11] E Sitwell Aspects of Modern Poetry (1934)

Froanna by Wyndham Lewis