Whatever happened to Henry Lamb?

She couldn’t see a trace of that former dazzling beauty in his battered face.

Henry Lamb was a complex person, witty, intelligent, temperamental, cynical, preceptive, passionate and occasionally cruel. He was very attractive to both sexes and he both fascinated and distressed his equally intelligent and discerning contemporaries. His moods were unpredictable. His relationship with Euphemia was stormy, they were both passionate and capricious. Had he been of a different disposition their relationship might have lasted longer and Euphemia wouldn’t have had to survive in Paris in the way she did. Although their marriage lasted less than a year, they married in May 1906 and it was over by May 1907, they kept in touch and remained friends and possibly lovers. We have seen that Henry Lamb took some responsibility for Euphemia when she was spiraling out of control in Paris, by writing to Roche in December 1907 and by going to Paris in August 1908 to fetch her back to London with Sir Walter Westley Russell. In 1909 the pair of them visited their cottage in Wiltshire and he painted a lovely languid watercolour of her. Because they didn’t divorce until 1928 their lives remained intertwined for some years.

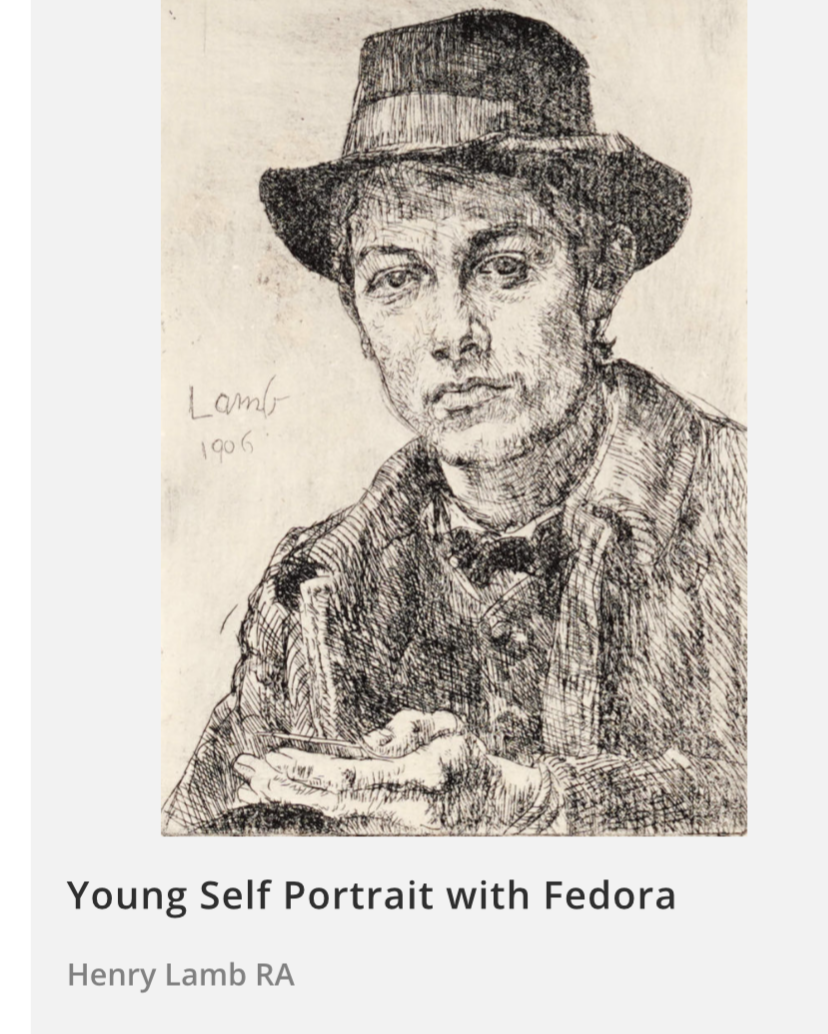

In the same way that Euphemia was attractive to a good many people, Henry was also famed for his devastating good looks as a young man. Vanessa Bell admired him as did her brother Adrian and Lytton Strachey was strongly attracted to him. Only Virginia Woolf noticed something cruel about him and referred to him as “the evil goat’s eye”. Henry’s egotism and vanity could have been the result of the fact that people found him extremely attractive and he had no difficulty attracting lovers. It does seem that his personality difficulties combined with his alluring beauty led him into some very destructive behaviours. Euphemia was his first victim but not his last. Although he continued to see Dorelia for over twenty years as a lover, there were many other lovers and conquests along the way, before he finally settled down and married Lady Pansy Packenham in 1928.

In Paris he left Euphemia for Dorelia, the mistress and common law wife of Augustus John. Henry continued to have a love affair with Dorelia for over twenty years; but it became clear that she was never going to leave Augustus John or their children for Henry. Henry was a frequent visitor to the John’s country houses at Alderney Lodge and Fryern Court. He even lived in Poole for a while to be near Dorelia at Alderney. Her son Romilly wrote that it was clear that the purpose of Henry’s visits was to see Dorelia and not Augustus. He was very popular with the children. Details of his mature love affair with Dorelia were recorded by the artist Dora Carrington during the 1920’s. Carrington was by this time Lytton Strachey’s companion and saw Henry and Dorelia regularly.

Carrington’s letters to Lytton from Ham Spray give us an insight into Henry’s maturing relationship with Dorelia.

‘A wire from Henry Lamb and Dorelia to say they were coming for tea. Dorelia looking very lovely, and in high spirits. Henry a little older perhaps and a little balder than the last time! I was completely knocked over by Dorelia and her beauty. She was very talkative and gay. We played the gramophone most of the time, drank mead and sloe gin and bottles of wine, played ping pong and went to bed very late. It was interesting to see Henry and Dorelia together. She fairly raps him over the knuckles when he gets fussy and laughs at his absurd conversation and rags him when he gets sententious.’[1]

Six months later she writes again,

‘Dorelia arrived at half past six. Henry came over. We again had a super dinner ending with crème brulee and two bottles of champagne and more sherry afterwards. Dorelia became completely boozed and very gay. Even Henry was less gloomy and rather amusing. We played Haydn, made endless jokes and talked without stopping. Somehow I thought it was the most lovely evening I’d ever spent. I wish you could have been with us. It was partly the femme Dorelia. I got a good many embraces from her, and one passionate recontre with Henry in the hall. But I preferred the former. Henry stayed the night. Poor Dorelia was rather ill the next morning after our debauch.’[2]

Although he later married Pansy, the friendship and love between him and Dorelia persisted. Tristan de Vere Cole, illegitimate son of Augustus John, recalled driving Dorelia to the hospital in Salisbury when Henry was dying. Whilst Dorelia may have been the person he loved most, Henry took other lovers, often with her blessing.

In 1908 Helen Maitland who was a close friend of Dorelia’s became his mistress, she was living in Paris with her mother and was part of their Bohemian circle. The relationship continued until 1910. Helen later married his very good friend Boris Anrep and Henry painted them as a family in 1920.

In 1910 Ottoline Morrell, the society hostess and Bloomsbury doyenne, fell in love with Henry. It was Dorelia who brought them together; hitherto Ottoline had been having an affair with Augustus John and Dorelia might have been seeking to distract Ottoline with Henry.

‘It was perhaps a half maternal instinct that pushed me towards this twisted and interesting figure.’

Ottoline wrote, but she found him irresistible, ‘like a vision of Blake.’

He was twenty seven and she was ten years older and married to the MP Philip Morrell. Ottoline wrote how difficult it was to get close to Henry,

‘and only by being very strong and generous, persistent and ignoring his bursts of fury could I get near him at all. He has however a very fine and beautiful nature threading through all his poor beaten vain sensitive self…John and his set have done much to ruin and deface him and to make him disbelieve in good.’

Ottoline was upset by his refusal to give up seeing Helen Maitland and by his protestations of love towards Dorelia, “all his heart is given to Dorelia”, she wrote in May 1910 when she fell in love with him. Falling in love with him was a torrid business,

‘For no one had such a power of tormenting a soul as Henry Lamb had. For half a day he would be angelic and enthrall one by his conversation, his humour and gaiety and his enjoyment of the moment, his wit and observation, his tenderness – then suddenly he would change and become a devil, full of spleen and cruelty, cutting one with as with a knife, with his rude behaviour and cruel words.’

Lytton Strachey who had been enamoured of Henry Lamb since their first meeting in 1905, also came back into Henry’s life at a dinner party given by Bertrand Russell and his wife in April 1910.

‘I was feeling dreadfully bored when I suddenly looked up and saw her (Ottoline) entering with Henry. I was never so astonished and didn't know which I was in love with most’ wrote Lytton.

Henry liked Lytton and invited him to sit for him and the two became friends. Henry was dissatisfied with his accommodation and studio in Fitzroy Street and Ottoline in an effort to keep him close invited him to come and live with her and Philip at their cottage, Peppard near Henley upon Thames, with a coach house down the road which he could use as a studio. Henry was delighted,

‘You have put me on such a footing that I can look all the difficulties straight in the face…I can chirp, grow fat, live where I will and paint what I like.’

Unbeknownst to Ottoline that Lytton was secretly in love with Henry, when things got tense between Henry and Phillip, she invited Lytton to come and stay too. In April 1911, Henry and Lytton spent a week together at her cottage near Henley. Lytton wrote to his brother James that,

‘Henry was more divine than ever, plump now (but not bald) and mellowed in the radiance of Ottoline. The menage is strange. Fortunately Philip is absent. Henry sleeps at a pub on the other side of the Green, and paints in a coach house rigged up by Ottoline with silks and stoves, a little further along the road’

Lytton described the week at Peppard as like “an interlude from the Arabian Nights.”

He returned again in the November and wrote,

‘My existence here is something new. I tremble to think what an “idyll” it might be.’

Both Ottoline and Lytton had fallen in love with Henry. The relationship with Ottoline and the friendship with Lytton continued until 1912. At this time Ottoline transferred her affections to Bertrand Russell, she found Henry’s moods and fluctuations in mental health difficult to manage. Similarly Lytton also found his moods difficult to cope with.

‘His state of mind baffles me, he seems to be completely indifferent to everything that concerns me, and yet expects me to be interested in every trifle of his life.’

and

‘He is the most delightful companion in the world – and the most unpleasant.’

Lytton wrote to his brother James in 1911.

Sexual tension was in the air; Lytton was homosexual, Henry heterosexual, but as Ottoline noted Henry “certainly cares more for Lytton” and “Lytton’s fancy was much tickled by Henry’s bawdiness.” Ottoline observed how Henry was flirting with Lytton who was charmed,

‘Lamb enjoyed leading him forth into new fields of experience.’

Quite how far the relationship went, is difficult to know. Lytton was convinced that Henry with his angelic smile and feminine beauty could be converted to bisexuality. Henry certainly introduced Lytton to his Bohemian milieu and the likes of Augustus John and Boris Anrep. Around this time Lytton started growing a beard and wearing an earring.

We do know that there was an unsuccessful trip to Doelan in Brittany where Lamb was accompanied by Boris Anrep and Dorelia’s sister Edie who he had taken along as a model. Henry complained bitterly about Edie.

‘A sudden enterprise made me carry off Dorelia’s sister with me…When she is posing there is a certain grim romance in painting that serene mysterious brow which I know to contain flat thoughtlessness and no trace of imagination and the far gazing eyes! I know they are too short sighted to see anything and they are glad of it. After all I must be grateful, the despised creature has repeatedly done me immense and rare services, it was a pity that I could accept them at the price of living with her at close quarters.’

Ottoline wrote,

‘Did you hear he (Henry) raped Dorelia’s sister?’

Presumably her informant was Lytton. Henry wrote that Lytton’s visit had been a failure and that he “simply moped and whined and funked in his room.”

In January 1912 having spent Christmas with Dorelia and John at Alderney Manor, Henry and Lytton were invited to Lulworth in Dorset with Rupert Brooke and Ka Cox. On this trip Ka fell for Henry and they evidently had an affair which led to Rupert Brooke becoming extremely jealous. When she came back from Lulworth, Ka told Rupert that she wanted to marry Henry. Rupert proposed to her and was refused and then he fell into “the most horrible kind of Hell, without sleeping or eating – doing nothing but suffering the most violent mental tortures which reacted on my body to such an extent, that after the week, I could barely walk.”

Henry left for London and Ka wanted to follow him but it was Lytton who persuaded her to stay and look after Rupert in his collapsed state of mental anguish.

Lytton wrote to Henry,

‘Ka came and talked to me yesterday between tea and dinner. It was rather a difficult conversation, but she was very nice and very sensible. It seemed to me clear that she was what is called “in love” with you – not with extreme violence so far, but quite distinctly. She is longing to marry you.’

Two days later, Lytton wrote again,

‘If you are not going to marry her, I think you ought to reflect a good deal before letting her become your mistress.’

Rupert described Henry to Ka as,

“someone more capable of getting hold of women than me, slightly experienced in bringing them to bed, who didn’t fool about with ideas of trust or ‘fair treatment’…The swine one gathers was looking around. He was tiring of his other women, or they of him. Perhaps he thought there’d be a cheaper and pleasanter way of combining fucking with an income than Ottoline…He cast dimly round. Virgins are easy game…He marked you down.”

This torrid affair does not reflect well on Henry. It seems that Henry was apt to use sex and conquest as a way of managing his aggressive depressions. Did the non-availability of Dorelia mean that he relished playing with other people and breaking up romantic relationships? We know that by February 1912 he was receiving treatment by Dr John Bramwell, a pioneer psychotherapist. Lytton’s brother James Strachey was the translator of Freud’s works into English and would have probably found him for Henry.

As to the question whether the relationship between Henry and Lytton became sexual there are allusions in the correspondence that it may have done.

On the 5th January 1912 in the middle of the Ka Cox affair, Maynard Keynes wrote to Duncan Grant, that Lytton “would grope him (Henry) under the table at meal times in view of all the ladies.”

In the summer of 1912 Lytton and Henry went on more trips together, to Cumberland and to Ireland. Lytton wrote to Henry during this period,

‘Won’t my papa come and open the door and take me into his arms again?’

After the failure of one of these trips, Lytton wrote Henry a letter disguised as a short story about an ape and a baboon who become great friends but are ultimately incompatible (reprinted in full in Appendix). There is a great deal of sexual innuendo in this letter and the fact that it was found in the archive of Helen Maitland Anrep rather than in Lamb’s main archive suggests that Lamb may have given it to Helen or Boris for safekeeping.

Henry’s reply to this missive which he sent in August 1912 contains a drawing; it is a cartoon depicting the two of them as ape like creatures in the jungle. Lytton is studying his vast penis and Henry farting a message into his dismayed face,

‘Best friends are not always best companions.’

Although the friendship cooled in intensity, Lytton continued to sit for Henry and in fact Henry’s most well known painting is a very unusual portrait of Lytton, full length with a stylized Hampstead Heath bursting through the window. It was finished just before the outset of the first World War. Lytton looks languid and as if his long limbs are boneless. It is an extremely good likeness of Lytton and conveys something of the enigma of their relationship.

Lytton and Ottoline consoled each other when the Henry star began to fade. Ottoline wrote to Bertie (her new lover) that Henry was “partly insane from egotism and vanity.” Ottoline and Philip bought Garsington Manor in 1915, partly as a country home and partly as a refuge for their friends who were conscientious objectors, such as Clive Bell. She installed the garden statue that she had commissioned from Jacob Epstein in 1912 in the gardens there, a statue of Euphemia Lamb.

Henry matured a great deal during the Great War. He became a close friend and mentor of the painter Stanley Spencer and in fact the two of them served in Salonika together. Henry enlisted as a medical orderly at Guy’s Hospital in 1914, but after a few months of dressing wounds he was encouraged to go back and complete his training and qualify as a doctor. He was promoted to Captain and saw action in France and Palestine. He was awarded the Military Cross for bravery. He was gassed just before the Armistice and invalided for a period, after which his health never was really good again. He could have remained a doctor but chose to return to being an artist and became a portrait artist for the remainder of his life.

He painted many society people including Sir Michael Sandler, Bryan Guinness and Diana Guinness, Evelyn Waugh, Sir Neville Chamberlain and Lady Megan Lloyd George.

Lady Diana Mosely remembered her sitting,

‘When I knew him there was no trace left of his youthful beauty of which one reads in books about his appearance before the first world war. He was a rather sour and cross man, possibly disappointed? I don’t know. Extremely spiteful about nearly everyone.’[3]

In 1928 he married Lady Pansy Packenham. It was evidently a happy marriage and he called her his “arch-angel”. She was beautiful, titled, clever and according to her niece Lady Antonia Fraser, rather vague and dreamy. Maybe it was this quality which allowed her to ignore the more difficult parts of his personality.

Sir Kenneth Clark wrote,

‘It was a pleasure to stay with him at Coombe Bissett because Pansy was such an angel, and the children were enchanting. But there was about him something sharp and bitter which prevented me from ever being wholly at ease with him; also, I suppose although I did not realise it at the time because he had been very much spoiled when he was a beautiful young man. He always used to say to me about his brother Walter, the secretary of the Royal Academy, “Be careful of Walter, he’s as cunning as a fox.” This might perhaps have been applied to him.’[4]

The affairs with Helen Maitland, Ottoline Morrel, Edie McNeil, Ka Cox and his casual treatment of Lytton Strachey suggest a man who found sexual conquest easy but intimacy more difficult to achieve; he seems to have achieved it with the unavailable Dorelia and finally in his marriage to Pansy. He and Euphemia seem similar creatures in their need to be admired and adored but both finding love and greater emotional intimacy more difficult to achieve.

Letter from Lytton Strachey to Henry Lamb

Dear Henry,

Once upon a time a friendship sprang up between an Ape and a Baboon. The Baboon was a somewhat melancholy monkey, mot generally popular, owing to his fastidious tastes and lackadaisical manners, but on the whole reputed to have a good heart. The Ape was young and agile; his form, though small, was elegantly moulded; and he was particularly attractive to the female monkeys of the neighbourhood, by virtue of the brilliant colouring and singular odour of those parts of his person which decency forbids me to name. He possessed, too, a remarkable accomplishment – the art of collecting the flowers of the forest into bouquets and garlands of such admirable beauty that none could behold them without delight. The elderly Orang Outangs were especially pleased by the harmonious tints and ingenious arrangements of these flowery confections and whatever he might produce of this kind – whether large or small, whether an elaborate bunch, a ceremonial garland, or a simple nosegay – he could always be sure to dispose of, in exchange for nuts and blandishments. The Baboon admired his friend’s art; but scandal whispered that he admired still more those portions of his frame to which I have above referred, which I blush to refer to again, and which no self-reflecting male monkey ever looked upon without complete indifference. Perhaps, however, it was neither the arts not the parts of the Ape that determined his friend’s affection, but some more subtle essence too delicately confounded for any but the most skilled anatomist of simian nature to describe with accuracy. As for the Ape, it is probable that what pleases him most in the Baboon was a brown beard of excellent proportion. Be that as it may, the friendship ripened rapidly, and soon the Ape and the Baboon were constantly to be seen together, swinging from the top of some high tree, cracking nuts in the shelter of some hollow trunk, or scampering down the forest glade one after the other, with the gayest grins imaginable. Some of his friends told the Baboon that he was unwise in his choice of companion; they said that Apes in general could never be depended upon and that this Ape in particular was known to be a most undesirable character; but the Baboon would not listen. “Whatever the rest of the family may be,” he said, “this member of it does not deserve your censure. Say what you will, I shall hold to my opinion, for I know him better than any of you. The Ape is a good Ape.” So the friendship continued though (as in all friendships) it was occasionally interrupted by a quarrel. Sometimes the quarrel was slight, sometimes it was serious, sometimes the Ape was at fault, sometimes the Baboon. I have heard that on one or two occasions the Baboon’s conduct was far from satisfactory and that he had promised the Ape with the most solemn vows never to lay a hand upon those curious organs which I have already twice been obliged to mention yet a third time; and that, under the influence of a reprehensible excitement, those vows were entirely forgotten. This I have heard; and I have also heard that the Baboon, on acknowledging his error was surprised and delighted by the gentleness and good humour which the Ape, after the first moments of natural anger, invariably showed. But let me turn away from this unpleasant subject. What the two friends particularly enjoyed was to leave their accustomed nests for a day or two, and to take a long ramble together in some unfamiliar part of the surrounding forest. Then their spirits rose wonderfully; the Baboon forgot his melancholy and whisked his tail; while the Ape, running in front, and smoothing the way for his companion, indulged in many remarkable antics and agreeable gesticulations. At last an expedition longer than all the rest was planned and undertaken. The monkeys started out with high hopes, and for several days wandered very happily among strange regions, where few of their kind had ever penetrated before. But suddenly there was a disaster….

Beyond this point, my dear Henry, in the history of those interesting animals, my memory does not carry me. Perhaps you can supply the rest.

Your

Lytton

[1] Letter from Carrington to Lytton 30/03/1925

[2] Letter from Carrington to Lytton 26/09/25

[3] Diana Mosely to Keith Clements 24/10/77 Tate archives

[4] Kenneth Clark to Keith Clements 22/10/77 Tate archives

Dorelia McNeill by Augustus John

Henry Lamb, Darsie Japp, Diana & Brian Guinness c1930